We must rethink our linear and simplistic ideas about cause and effect. This is true not only for the physical world, but even more critically, for the nature of consciousness, or as some would call it, the spiritual world. The following poem continues my explorations on these matters.

Mewzen on Kawz in Effeks

Hoeshaya 8:4: "They ordained officers but I [God] did not know."

How kan this be?

Wut iz it God duz not kno?

Thus we ar telld:

The hewman Seel in Addom iz non-exxisten.

Oenlee az it seek holeeness,

Oenlee az it bilden knowen,

Oenlee az it persu justis,

Duz it rizen tu exxisten.

Els it stumbel in degreez a darkness

And exxert itsellz tu no effeks.

Addom themsell iz mere indetermennus.

The Prezzens a God alone giv direkten tu the werl.

And wut iz not tu God will fall awway, debree,

Az a skatter a leevz sterrd by a winden,

Az a pile ov ashez, a life bernd awway.

That wich livz in darkness, in Addom

Haz no fewcher in Godz evolven werlz.

It shudder and flikkerz, it vibe and reverb

Beneeth the kawz and effeks a Life.

The vast and tedeyus hewman laberz

Ar but soyelz in wich the dellakkut frute

Ov the hewman Seel iz seed and rooted.

This sivvillazzaten, this moest ov wut we see

Iz insubstanshel, iz a dezzert merrozh,

Like dust devvelz sterrd by owwer on-rushen Lor.

The Ejjipshenz, the Babballoneyanz, and the Romenz,

The inkwizzatterz, the zarz, the notseez,

The iyattolahz, thay will all tare down,

But the Lor iz lift Hem holee wunz.

And the tru, the holee werk kontinnewz

And, nevver dout, but nuthing haz bin loss.

Sunday, December 31, 2006

Friday, December 22, 2006

Opening stanza to (Stormz and Graevz)

What follows is transcribed out of my notebooks. It’s a kind of peek into my literary and conceptual processes, as I try to convert threshold experiences into known language. It is really a process of translation. The Biblical Prophets, Dante, Milton, Shelley, Blake, Bialek: they were all expert translators, and they are my guides.

Two simple notes for those of you who may try to read this:

Words in parentheses are uncertain. Often I come up with a series of alternatives as I try to unpack and explore the poetic experience (ie, the thought-vision) shaping the image and action. Not infrequently, there is no “correct” word, the poetic experience being multi-faceted. In this case, the group of alternatives, as a whole, can be thought of as being the best estimate of the experience. But, God knows, my poetry is hard enough as it is, so, ultimately, I pare it down to produce a fair copy of the poem.

Phrases in brackets are also uncertain, as with words in parens.

(Down marbel kollonaedz that (sparkel)(boyel)(plunj) like (wotterfallz)(kristel kaskaedz)

Eech likwid kollum splashing at owwer feet,

A spray of lite, mika and (korts)(kworts),

Iz a (gaetway) intu [the Pardaes Uddoniy][owwer Pardaes breet*][owwer Pardaes, a breet*].

* “breet:” holee kontrakt; kuvvannent

A week later, I revised the above to this:

Ar thay (marbel)(skulpted)(ruwend) kollonnaedz? Ar thay (kristel)(marbel) kaskaedz?

Ar thay likwid (kollumz)(skroelz)(duenz) (unroling at)(washing tu) owwer feet?

A spray ov lite (;)(frum) mika and korts,

[A fomee serf][And a kwiyer ov waevz][And the rumbel and mermer] (at)(by) [the Gaets ov the See].

And as I try to focus the above, this is what I’m currently thinking will work:

Ar thay marbel kollonnaedz? Ar thay kristel kaskaedz?

Ar thay likwid skroelz unroling at owwer feet?

A spray ov lite, mika and korts,

In a kwiyer ov waevz at the Gaets ov the See.

Two simple notes for those of you who may try to read this:

Words in parentheses are uncertain. Often I come up with a series of alternatives as I try to unpack and explore the poetic experience (ie, the thought-vision) shaping the image and action. Not infrequently, there is no “correct” word, the poetic experience being multi-faceted. In this case, the group of alternatives, as a whole, can be thought of as being the best estimate of the experience. But, God knows, my poetry is hard enough as it is, so, ultimately, I pare it down to produce a fair copy of the poem.

Phrases in brackets are also uncertain, as with words in parens.

(Down marbel kollonaedz that (sparkel)(boyel)(plunj) like (wotterfallz)(kristel kaskaedz)

Eech likwid kollum splashing at owwer feet,

A spray of lite, mika and (korts)(kworts),

Iz a (gaetway) intu [the Pardaes Uddoniy][owwer Pardaes breet*][owwer Pardaes, a breet*].

* “breet:” holee kontrakt; kuvvannent

A week later, I revised the above to this:

Ar thay (marbel)(skulpted)(ruwend) kollonnaedz? Ar thay (kristel)(marbel) kaskaedz?

Ar thay likwid (kollumz)(skroelz)(duenz) (unroling at)(washing tu) owwer feet?

A spray ov lite (;)(frum) mika and korts,

[A fomee serf][And a kwiyer ov waevz][And the rumbel and mermer] (at)(by) [the Gaets ov the See].

And as I try to focus the above, this is what I’m currently thinking will work:

Ar thay marbel kollonnaedz? Ar thay kristel kaskaedz?

Ar thay likwid skroelz unroling at owwer feet?

A spray ov lite, mika and korts,

In a kwiyer ov waevz at the Gaets ov the See.

Sunday, November 26, 2006

From: Ammung the Ruwenz ov the Tempel, I Herd...

I have always felt that everything that can be known, is revealed in the waves of the ocean...

Open Wun Skroel, Enter the Ferst Wave

Shabbat Pesukh khoel Ha-mowaed 5760

Shakhreet Shemmona Esray

And then I kame tu the Grate See.

And the darkness in the forres

Reseeded intu oek shrub

And yello flowwer brume.

Then sharp ej beech grass rubbd my shinz,

And the roer ov brakerz washt akross my fase.

My foutprints krosst the beech in her singing,

Her armz spred wide with fraktel pattern tallit*.

*shawl; sandz

She dessendz and the wotterz rize up tu her,

Erasing the kruwelteez that hav echt thaer furroez

Intu her fase. Re-riets her histerree evree momen.

Unkovverz her seel in salm an immerzhen.

I lay with her, lips tu her lips,

Brest tu my brest; the shape ov my boddee

Imprest in her Soel, an expans ov sand.

The see sang its versez tu me by thowzendz,

Wave after wave, vers after vers,

Storee after storee, letter after letter,

Era after era, the brakerz the song,

Reveeled tu eech Soel and tu all the werldz,

And hu evver iz reddee tu approech tu lissen.

I gaezd on the skroelz unroeling befor me

Trying tu interpret thaer infinnit voise.

Eech skroel az it opend reveeld ferther skroelz,

Eech werd expanding tu hewman lievz,

Eech skroel re-roeling and klozing at my feet,

Swerling a foming arrownd my aenkelz.

I reecht down tu gather and lift up a handful.

Between my feengerz a dimend kaskade.

I splash my fase, senshuwus and koeld.

The songz kaskaden; thay rize and re-spirel,

And I, huze steps will be eraest frum the beech,

Konkluden my praerz, I steppt back and bow.

Open Wun Skroel, Enter the Ferst Wave

Shabbat Pesukh khoel Ha-mowaed 5760

Shakhreet Shemmona Esray

And then I kame tu the Grate See.

And the darkness in the forres

Reseeded intu oek shrub

And yello flowwer brume.

Then sharp ej beech grass rubbd my shinz,

And the roer ov brakerz washt akross my fase.

My foutprints krosst the beech in her singing,

Her armz spred wide with fraktel pattern tallit*.

*shawl; sandz

She dessendz and the wotterz rize up tu her,

Erasing the kruwelteez that hav echt thaer furroez

Intu her fase. Re-riets her histerree evree momen.

Unkovverz her seel in salm an immerzhen.

I lay with her, lips tu her lips,

Brest tu my brest; the shape ov my boddee

Imprest in her Soel, an expans ov sand.

The see sang its versez tu me by thowzendz,

Wave after wave, vers after vers,

Storee after storee, letter after letter,

Era after era, the brakerz the song,

Reveeled tu eech Soel and tu all the werldz,

And hu evver iz reddee tu approech tu lissen.

I gaezd on the skroelz unroeling befor me

Trying tu interpret thaer infinnit voise.

Eech skroel az it opend reveeld ferther skroelz,

Eech werd expanding tu hewman lievz,

Eech skroel re-roeling and klozing at my feet,

Swerling a foming arrownd my aenkelz.

I reecht down tu gather and lift up a handful.

Between my feengerz a dimend kaskade.

I splash my fase, senshuwus and koeld.

The songz kaskaden; thay rize and re-spirel,

And I, huze steps will be eraest frum the beech,

Konkluden my praerz, I steppt back and bow.

Saturday, November 18, 2006

A message from beyond the body

This poem won an award in the 2005 Reuben Rose International Competition.

Tahharra: Borderz

begun 10 Tishray, 5764

Frum I, hu am not,

Tu yu, hu ar not;

I, hu hav seest tu be

Tu yu, hu ar no mor.

Havving taken wun step up the infinnit ladder

Owwer lumennus boddeez tranzmit thaer knowenz...

A bowndree ov C,

Ware we stand, this side

Ov the ark ov the Lor.

With theze eyz

The long ark ov dezzerted beech

Seen frum on hi, the Truro duenz.

And the koeld Atlantek, ultra mareen,

Rippeld in the tenshenz ov plannettaree moeshenz.

Between the infinnit graenz ov sand

And the kolapsing waevz ov rezistless momentum,

A thin wite line of lasee foem,

Swaying and swerling a dellikut border...

That iz the kerten, and behiend it I stand,

The not me of lite in the not yu ov lite

Within the arken Torrah and Divvine gaetwayz.

With eyz kuvverd by karben** shardz

** utherz say "potterree"

The Hi Preest prepaerz,

Hiz breth groez shallo.

Hiz fase deth pale, handz almoest fleshless,

Hiz skin tranzlusen az skraept parchmen.

Kloethd in a robe ov fine woven kotten,

A brusht wite brokade and thik kotten belt.

A brusht wite skull kap, kotten brokade

Its dansing liyonz and leeping deer.

Hiz naelz ar klippt, hiz wite beerd trimmd,

He immerst 3 tiemz in a chill mikvah.**

** ritchuwel baething

The Hi Preest prepaerz.

He seesez tu breeth;

The waevlike moeshen ov hiz puls groez long.

He taeks a last step, an endless instant

Az he enterz the ark ov Divvine Prezzens.

That iz the kerten, and behiend it I stand,

The not me ov lite in the not yu ov lite,

Boddeez ov lite within the tranzlusent arks ov Torrah.

Tahharra: Borderz

begun 10 Tishray, 5764

Frum I, hu am not,

Tu yu, hu ar not;

I, hu hav seest tu be

Tu yu, hu ar no mor.

Havving taken wun step up the infinnit ladder

Owwer lumennus boddeez tranzmit thaer knowenz...

A bowndree ov C,

Ware we stand, this side

Ov the ark ov the Lor.

With theze eyz

The long ark ov dezzerted beech

Seen frum on hi, the Truro duenz.

And the koeld Atlantek, ultra mareen,

Rippeld in the tenshenz ov plannettaree moeshenz.

Between the infinnit graenz ov sand

And the kolapsing waevz ov rezistless momentum,

A thin wite line of lasee foem,

Swaying and swerling a dellikut border...

That iz the kerten, and behiend it I stand,

The not me of lite in the not yu ov lite

Within the arken Torrah and Divvine gaetwayz.

With eyz kuvverd by karben** shardz

** utherz say "potterree"

The Hi Preest prepaerz,

Hiz breth groez shallo.

Hiz fase deth pale, handz almoest fleshless,

Hiz skin tranzlusen az skraept parchmen.

Kloethd in a robe ov fine woven kotten,

A brusht wite brokade and thik kotten belt.

A brusht wite skull kap, kotten brokade

Its dansing liyonz and leeping deer.

Hiz naelz ar klippt, hiz wite beerd trimmd,

He immerst 3 tiemz in a chill mikvah.**

** ritchuwel baething

The Hi Preest prepaerz.

He seesez tu breeth;

The waevlike moeshen ov hiz puls groez long.

He taeks a last step, an endless instant

Az he enterz the ark ov Divvine Prezzens.

That iz the kerten, and behiend it I stand,

The not me ov lite in the not yu ov lite,

Boddeez ov lite within the tranzlusent arks ov Torrah.

Friday, November 10, 2006

RE: the poem: Guerden ov Addomz (see 10/26/06)

Reb Rick Kool wrote to me, asking:

So what is it that is written in our cells that we drag up the hill? The search for the peaceful place, the search for the garden with food (all kinds of foods for mind and body), or is it that our cells tell us to stir up dust?

In answering him, I thought maybe it would be of interest to all of you, so here it is:

I guess I would have to answer that, on the first level, the poem attempts to unlock these kind of questions, rather than provide answers. But then again, I hate writers that spew out the copped-out, bullshit company line that "art and literature have no meaning except what each reader/viewer gives it." That's just so much hogwash in a bucket.

So I am glad if this poem inspires questions, but if that's all it does, it's a failure. If art/literature is to be more than decoration or entertainment, if it is to take leadership responsibility for making this world a better place, the author must be able to clearly convey intentions (in-tensions) and meanings, and not merely create questions, ambiguities, and bizarreties.

Technically, I am merging/superimposing into a single picture a few worlds: 1) this, the one we see with our eyes; 2) the after-death state which we cannot see at all with any certainty; 3) the Biblical-spiritual world that provides us with images of some kind of original (or pre-world) paradise, that may also be, 4) a Divine state of peace and perfection that is immanent but hidden.

We are the tillers of this soil, this world, but yet we hardly know what fruit it is we grow or harvest. Indeed, we are so busy, so overwhelmed even, with the details, that we hardly have the time, much less the vision, to contemplate what, if any, are the enduring impacts of our presence and our work here. We have hardly the time or the vision to consider that, as many believe, we stand in the Presence of the Divine, and yet, grievously, we see with our eyes how shameless our behavior can be. Many also believe the Messiah has come, and yet, grievously, we see with our eyes that these are not Messianic times, at least by any definition I can understand.

Perhaps with these kinds of meditations we can begin to remove the veil from our eyes, a curtain upon which is projected this obvious world, but which separates us from higher states of knowing and being. Many say, "no, there is only this world, and it is not (but) a veil." They say there is nothing deeper, nothing Divine, nothing Messianic to see or to know.

But I have seen the veil pulled back, and I am trying to address that experience and convey it, both for those who don't believe there is anything beyond this world, and for those who have seen beyond, and want to see more. The problem is, visionary experiences transcend our rationality, and thus can't be conveyed in simple, or literal, or rationalistic modalities. I'm not interested in telling about the experience. Plenty of others have done that. I want to generate a reality transcending experience in the reader! My response is to construct linguistic forms that stretch, or tear, the fabric of language, and that superimpose multiple states and places. By partially emulating the "visionary" experience, perhaps I can literarily (and literally) activate or stimulate it. I don't know what else to do, to try to help people see thru, or beyond, that which appears so opaque, so impenetrable, so insurmountable.

But to attempt to achieve such results in one way or another is absolutely necessary. Whether I succeed or fail is another issue entirely. How else are we to be inspired to change, to do better, if we cannot begin to glimpse the Divine Presence beyond the veil?

So what is it that is written in our cells that we drag up the hill? The search for the peaceful place, the search for the garden with food (all kinds of foods for mind and body), or is it that our cells tell us to stir up dust?

In answering him, I thought maybe it would be of interest to all of you, so here it is:

I guess I would have to answer that, on the first level, the poem attempts to unlock these kind of questions, rather than provide answers. But then again, I hate writers that spew out the copped-out, bullshit company line that "art and literature have no meaning except what each reader/viewer gives it." That's just so much hogwash in a bucket.

So I am glad if this poem inspires questions, but if that's all it does, it's a failure. If art/literature is to be more than decoration or entertainment, if it is to take leadership responsibility for making this world a better place, the author must be able to clearly convey intentions (in-tensions) and meanings, and not merely create questions, ambiguities, and bizarreties.

Technically, I am merging/superimposing into a single picture a few worlds: 1) this, the one we see with our eyes; 2) the after-death state which we cannot see at all with any certainty; 3) the Biblical-spiritual world that provides us with images of some kind of original (or pre-world) paradise, that may also be, 4) a Divine state of peace and perfection that is immanent but hidden.

We are the tillers of this soil, this world, but yet we hardly know what fruit it is we grow or harvest. Indeed, we are so busy, so overwhelmed even, with the details, that we hardly have the time, much less the vision, to contemplate what, if any, are the enduring impacts of our presence and our work here. We have hardly the time or the vision to consider that, as many believe, we stand in the Presence of the Divine, and yet, grievously, we see with our eyes how shameless our behavior can be. Many also believe the Messiah has come, and yet, grievously, we see with our eyes that these are not Messianic times, at least by any definition I can understand.

Perhaps with these kinds of meditations we can begin to remove the veil from our eyes, a curtain upon which is projected this obvious world, but which separates us from higher states of knowing and being. Many say, "no, there is only this world, and it is not (but) a veil." They say there is nothing deeper, nothing Divine, nothing Messianic to see or to know.

But I have seen the veil pulled back, and I am trying to address that experience and convey it, both for those who don't believe there is anything beyond this world, and for those who have seen beyond, and want to see more. The problem is, visionary experiences transcend our rationality, and thus can't be conveyed in simple, or literal, or rationalistic modalities. I'm not interested in telling about the experience. Plenty of others have done that. I want to generate a reality transcending experience in the reader! My response is to construct linguistic forms that stretch, or tear, the fabric of language, and that superimpose multiple states and places. By partially emulating the "visionary" experience, perhaps I can literarily (and literally) activate or stimulate it. I don't know what else to do, to try to help people see thru, or beyond, that which appears so opaque, so impenetrable, so insurmountable.

But to attempt to achieve such results in one way or another is absolutely necessary. Whether I succeed or fail is another issue entirely. How else are we to be inspired to change, to do better, if we cannot begin to glimpse the Divine Presence beyond the veil?

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Tahara: "purities," also used in the sense to prepare a body for burial

Deer Wunzelz and Rappunzelz,

There's nothing like good poesy. Well, anyway... today, I'm not uploading the one that refers to Darcy Thomson's On Growth and Form. That one's titled "Lamment ov the Hi Preest." It happened to me while walking my son Cal to school. Aaaaannnnd, I'm not uploading the one that explores, in an imagistic manner, the way in which randomness and determinism are simply two sides of a divine coin. It begins with a cool epigram from Zohar 1:15b, "The letters and vowel-points follow (Him) in their singing... like an army at the behest of the king."

Instead, this (which was recently published in the journal Sh’ma)...

Tahharrah: Boddeez ov Lite

week ov Va'yera, (Genesis 18-22)

Thare iz a man, hiz boddeez wer lite.

Wen he sat in hiz hows, mingeld with eevning,

Hiz boddee ar shaddoez in the pajez ov a bouk.

Wen he wokkt on the way, hiz chields befor him,

Hiz boddee iz a darkness aggenst the briten sun.

Wen he praez with hiz minyen, wisper and wunder,

Hiz boddee ar not, but a fluttering shawl.

Ware he sell frum hiz skreen owt tu the markets,

He wer fleshee fasez, and hevvee armz.

He haz wokkt in feeldz, furro and klod,

The raen a dripping down hiz shivver ov boenz.

This iz the man and hiz boddeez ov lite.

Eech benden shape and eech deegree ov thikness

Iz a vael, abstrakt on the Hevvenlee pallas.

Eech gate tu Hevven iz thin az a shaddo,

Like a pawlish marbel, likwid and smooth.

Eech windo dissolvz in a prizzem ov lite,

An oeshen ov unprediktabbel glints.

It's wallz ar kerv in a mennee foelden kerten,

Lase within lase ov intrekkut dezine.

With iyz, the man will not see a way in.

Kaerful, methoddek, intense reppattishen

Ov lissen and feel, a strikt hullakhah*,

* Jewish law; divine behavior patterns

Such a dellakut tuch on a flutter ov shawlz.

Like lips slo karressing her foerhed, her nape,

Her shoelderz, her brests, such a slo karress;

Downwerd, downwerd, in erottek foeldz,

Lips barelee tuch, all breth and trembel...

So the man ov lite, hiz boddeez ov deziyer

Muving ekstattek* in the vaelz ov Uddoniy.

* the fizzekz ov it iz, mor propperlee

"Muving diskontinnuwus"

There's nothing like good poesy. Well, anyway... today, I'm not uploading the one that refers to Darcy Thomson's On Growth and Form. That one's titled "Lamment ov the Hi Preest." It happened to me while walking my son Cal to school. Aaaaannnnd, I'm not uploading the one that explores, in an imagistic manner, the way in which randomness and determinism are simply two sides of a divine coin. It begins with a cool epigram from Zohar 1:15b, "The letters and vowel-points follow (Him) in their singing... like an army at the behest of the king."

Instead, this (which was recently published in the journal Sh’ma)...

Tahharrah: Boddeez ov Lite

week ov Va'yera, (Genesis 18-22)

Thare iz a man, hiz boddeez wer lite.

Wen he sat in hiz hows, mingeld with eevning,

Hiz boddee ar shaddoez in the pajez ov a bouk.

Wen he wokkt on the way, hiz chields befor him,

Hiz boddee iz a darkness aggenst the briten sun.

Wen he praez with hiz minyen, wisper and wunder,

Hiz boddee ar not, but a fluttering shawl.

Ware he sell frum hiz skreen owt tu the markets,

He wer fleshee fasez, and hevvee armz.

He haz wokkt in feeldz, furro and klod,

The raen a dripping down hiz shivver ov boenz.

This iz the man and hiz boddeez ov lite.

Eech benden shape and eech deegree ov thikness

Iz a vael, abstrakt on the Hevvenlee pallas.

Eech gate tu Hevven iz thin az a shaddo,

Like a pawlish marbel, likwid and smooth.

Eech windo dissolvz in a prizzem ov lite,

An oeshen ov unprediktabbel glints.

It's wallz ar kerv in a mennee foelden kerten,

Lase within lase ov intrekkut dezine.

With iyz, the man will not see a way in.

Kaerful, methoddek, intense reppattishen

Ov lissen and feel, a strikt hullakhah*,

* Jewish law; divine behavior patterns

Such a dellakut tuch on a flutter ov shawlz.

Like lips slo karressing her foerhed, her nape,

Her shoelderz, her brests, such a slo karress;

Downwerd, downwerd, in erottek foeldz,

Lips barelee tuch, all breth and trembel...

So the man ov lite, hiz boddeez ov deziyer

Muving ekstattek* in the vaelz ov Uddoniy.

* the fizzekz ov it iz, mor propperlee

"Muving diskontinnuwus"

Friday, November 03, 2006

New verses for the Zohar

So here's something I'm working on. This is an excerpt from a long semi-narrative poem called The Pardaes Dokkumen. It is the first 2 of 4 stanzas, but I thought 22 lines was enough to begin with here.

Context: There is a story (midrash) in Talmud (~2nd-5th C. CE) of 4 sages who ascend to "pardaes." This word can be translated as "garden" or "paradise" in its most obvious interpretations, but the midrash itself is very enigmatic. Of the 4 sages who ascend, one comes back an apostate, one comes back apparently mad, one doesn't come back (suicide? dead?), and one comes back "whole." The Zohar (~13th C. CE) picks up on the Pardaes midrash, directly and indirectly in many of its passages - mostly tangential expansions on the story. Also, the Zohar occasionally cloaks a great sage in the appearance of a peasant or lowly worker. "The Pardaes Dokkumen" draws on both Talmud and Zohar, as it reframes the story. I hope that gives you enough references points to read this excerpt.

Plowmen with Taelz

A donkee driver sed,

"I met a plowman reterning frum feeldz,

"Hu sed, ‘This partikkuler vallee iz flud,

‘And the oxxen ar serlee and I hav plow

‘The muk and the klay intu thik slerree.

‘Up tu my waest I hav groen and drivven

‘The beests, foemen at nostrel and kikken;

‘The plow in my handz, a sord tu the erth.

‘That iz the Torrah ov my narro vale.

‘The ferro ar fludden and no wun kan dissern

‘The seed frum the staen in the lienz I skribe.'"

A wotter kareyer sed,

"I meet a plowman a reternen frum feelz.

"He will say, ‘For jennerratenz I am plow this expanz.

‘My lingz ar groen frum its oxxide dust.

‘In morning its salt iz kurst on my iyz.

‘My fout print rekorden on the dune and drift.

‘My skin a reenkel az my plow iz reenkel.

‘Wut I du tu the lan, it duz tu me.

‘That iz the Torrah ov this endless span.

‘The sun and the wind strip off owwer raen.

‘We kut owwer ferro; thay bekum owwer grave.'"

Context: There is a story (midrash) in Talmud (~2nd-5th C. CE) of 4 sages who ascend to "pardaes." This word can be translated as "garden" or "paradise" in its most obvious interpretations, but the midrash itself is very enigmatic. Of the 4 sages who ascend, one comes back an apostate, one comes back apparently mad, one doesn't come back (suicide? dead?), and one comes back "whole." The Zohar (~13th C. CE) picks up on the Pardaes midrash, directly and indirectly in many of its passages - mostly tangential expansions on the story. Also, the Zohar occasionally cloaks a great sage in the appearance of a peasant or lowly worker. "The Pardaes Dokkumen" draws on both Talmud and Zohar, as it reframes the story. I hope that gives you enough references points to read this excerpt.

Plowmen with Taelz

A donkee driver sed,

"I met a plowman reterning frum feeldz,

"Hu sed, ‘This partikkuler vallee iz flud,

‘And the oxxen ar serlee and I hav plow

‘The muk and the klay intu thik slerree.

‘Up tu my waest I hav groen and drivven

‘The beests, foemen at nostrel and kikken;

‘The plow in my handz, a sord tu the erth.

‘That iz the Torrah ov my narro vale.

‘The ferro ar fludden and no wun kan dissern

‘The seed frum the staen in the lienz I skribe.'"

A wotter kareyer sed,

"I meet a plowman a reternen frum feelz.

"He will say, ‘For jennerratenz I am plow this expanz.

‘My lingz ar groen frum its oxxide dust.

‘In morning its salt iz kurst on my iyz.

‘My fout print rekorden on the dune and drift.

‘My skin a reenkel az my plow iz reenkel.

‘Wut I du tu the lan, it duz tu me.

‘That iz the Torrah ov this endless span.

‘The sun and the wind strip off owwer raen.

‘We kut owwer ferro; thay bekum owwer grave.'"

Friday, October 27, 2006

What is this paradise of bitter fruits?

Ritual and reason serve the same purposes. What follows is neither ritual nor reason, at least in the limited and traditional sense of those concepts...

I. The Guerden ov Addomz

We hav kum tu this guerden tu gather frute;

We doent kno wut frute; we doent kno this gena.*

* "garden" in Hebrew

We hav kum tu this hilltop, so perfektlee peesful,

But we see with owwer eyz it iz not peesful at all.

This iz the Plase and this iz the Trueth,

This Plase we kno not, nor kno we its Trueth.

We hav kum tu pluk frute, but in owwer kliming

We hav stirrd up dust and we hav shed (owwer) blud.

Guerden ov frute so still and begiling

Plase ov pees so stunninglee fraegrent,

I assend with my oderz; thay ar ritten in my sellz.

Distrakten and distorten I will arrive.

I. The Guerden ov Addomz

We hav kum tu this guerden tu gather frute;

We doent kno wut frute; we doent kno this gena.*

* "garden" in Hebrew

We hav kum tu this hilltop, so perfektlee peesful,

But we see with owwer eyz it iz not peesful at all.

This iz the Plase and this iz the Trueth,

This Plase we kno not, nor kno we its Trueth.

We hav kum tu pluk frute, but in owwer kliming

We hav stirrd up dust and we hav shed (owwer) blud.

Guerden ov frute so still and begiling

Plase ov pees so stunninglee fraegrent,

I assend with my oderz; thay ar ritten in my sellz.

Distrakten and distorten I will arrive.

Saturday, October 07, 2006

Concerning Allen Ginsberg's poem "Howl", part 3 of 3

Lies, Illusions, Fake Madness, Fake Art

Part 3

And from here we can finally confront the fourth level of dishonesty in this poem. The poem presents itself, and is intended to be seen, as the scribblings and desperate cry of just such a mad artist at the margin of sanity, or beyond. Because Ginsberg's readership is so primed by an absurd poetics that establishes madness as a qualifying necessity for artistic greatness, the minions bow down in awe. Here it is! The recovered writings of a mad prophet. But like faux marble, scratch the false colors, even with a dull knife, and they flake off.

The poet is not mad and there is nothing honest about the perception of madness he creates. If indeed the world had defeated him, and this was his last half-sane cry, perhaps we could find meaning in his words, and surely we would feel empathy for his broken spirit. But the poet is not defeated. The facts of his life speak loudly and clearly to the contrary. Ginsberg was a fighter and talented self-promoter to the very end. No, this is a paean to self-indulgence, with cynical disregard for the truth

So why is Howl so popular? Although I believe I have laid out some partial answers already, frankly, I ask the question, not to seek an answer, but to expose the real question. What has gone wrong with our literary standards, that we have lost the desire for exemplary art? Why is not moral grandeur the defining feature of our literature?

There is only one way to answer these two questions, and that is to throw off this shabby, ill-fitting and confining garment we call 20th century literature. We need to once again take responsibility for our words and the words that we read and endorse. Authors, not readers, are the creators of meaning. And those authors that take responsibility for the value of their words, will also take responsibility for creating pathways into our future.

Where are those great ones that can imagine a way from here to a desirable future? We have plenty of piddlers who can rant on about the morass and despair they live in. Enough of lies and narcissism, cynicism and despair! If our intentions do not have a clear purpose and meaning, and if that purpose and meaning is not essentially ethical, then we're not ready to sit down and write. Paraphrasing the words of Frederick Turner in his introduction to The New World, "If we're not prepared to imagine a better future, how can we possibly create one?"

Part 3

And from here we can finally confront the fourth level of dishonesty in this poem. The poem presents itself, and is intended to be seen, as the scribblings and desperate cry of just such a mad artist at the margin of sanity, or beyond. Because Ginsberg's readership is so primed by an absurd poetics that establishes madness as a qualifying necessity for artistic greatness, the minions bow down in awe. Here it is! The recovered writings of a mad prophet. But like faux marble, scratch the false colors, even with a dull knife, and they flake off.

The poet is not mad and there is nothing honest about the perception of madness he creates. If indeed the world had defeated him, and this was his last half-sane cry, perhaps we could find meaning in his words, and surely we would feel empathy for his broken spirit. But the poet is not defeated. The facts of his life speak loudly and clearly to the contrary. Ginsberg was a fighter and talented self-promoter to the very end. No, this is a paean to self-indulgence, with cynical disregard for the truth

So why is Howl so popular? Although I believe I have laid out some partial answers already, frankly, I ask the question, not to seek an answer, but to expose the real question. What has gone wrong with our literary standards, that we have lost the desire for exemplary art? Why is not moral grandeur the defining feature of our literature?

There is only one way to answer these two questions, and that is to throw off this shabby, ill-fitting and confining garment we call 20th century literature. We need to once again take responsibility for our words and the words that we read and endorse. Authors, not readers, are the creators of meaning. And those authors that take responsibility for the value of their words, will also take responsibility for creating pathways into our future.

Where are those great ones that can imagine a way from here to a desirable future? We have plenty of piddlers who can rant on about the morass and despair they live in. Enough of lies and narcissism, cynicism and despair! If our intentions do not have a clear purpose and meaning, and if that purpose and meaning is not essentially ethical, then we're not ready to sit down and write. Paraphrasing the words of Frederick Turner in his introduction to The New World, "If we're not prepared to imagine a better future, how can we possibly create one?"

Thursday, October 05, 2006

Concerning Allen Ginsberg's poem "Howl", part 2 of 3

Part 2

Continued from 10/4/06

But this lie, about who the great ones are, is the necessary first step into the poetics of dissipation and futility.

The second misapprehension, one step below the surface, is the self-referential justification of the first lie. Here we learn from the fake prophet that the world is unredeemable, so much so that the only, or best, or at least the most "artistic" response to these times is rejection and withdrawal. The world is too terrible and the sensitive soul (oh woe, oh woe) is crushed by it.

There are indeed many people crushed by the harshness of the world. Each of these people represents a great diminishment of what "could be." They are deserving (and demanding) of our help. They require an active response to bring healing, and are not to be silenced and shunted off in locked corners.

But, this is surely not the point of the poetics that guided Howl. The poet is not making a plea for more kindness. Nor is he guiding our steps through or around the morass of oppression, violence, and insensitivity that confronts us. Nor is he lamenting our ruin and loss. No! He is reveling in drunken and drugged-out disregard and disdain. His burning question to the reader is, "What is your drug of choice?" Those committed to dissipation and futility will smile and say, "Yes! That's the main question. Why not? What else is there?"

Yes indeed! Many people feel this way, and I have too, on occasion. But the fact that people think this is an honest response, and not merely honest but worthy of a whole poetics; this is what causes me to worry about our state of affairs.

And this fact takes us into the real inner workings of dishonesty and cynicism in this poem: the fable that has long equated inspiration with madness. This idea, articulated at least as long ago as German "Sturm and Drang" and found in English romanticism (although none of the romantics I've read were mad), became the calling card of dada and surrealism and their numerous offshoots. It is embedded in the popular mythologizing about the artist, in spite of the fact that one is hard-pressed to find meaningful examples. With a notable exception or two, like Nerval, the best we can do is point to some second-rate writers and local losers like Pound and Artaud and Plath. Ginsberg has simply summed up a long history of illusion and sloppy thinking. If we take Howl seriously we can only conclude that art and literature are degenerate, self-destructive activities, and that imagination and creativity are signs of disease, worthy of close medical monitoring at their first appearance. And yet this foolishness is the modus operandi of Howl, and a cornerstone of the poetic imagination of this century.

Continued from 10/4/06

But this lie, about who the great ones are, is the necessary first step into the poetics of dissipation and futility.

The second misapprehension, one step below the surface, is the self-referential justification of the first lie. Here we learn from the fake prophet that the world is unredeemable, so much so that the only, or best, or at least the most "artistic" response to these times is rejection and withdrawal. The world is too terrible and the sensitive soul (oh woe, oh woe) is crushed by it.

There are indeed many people crushed by the harshness of the world. Each of these people represents a great diminishment of what "could be." They are deserving (and demanding) of our help. They require an active response to bring healing, and are not to be silenced and shunted off in locked corners.

But, this is surely not the point of the poetics that guided Howl. The poet is not making a plea for more kindness. Nor is he guiding our steps through or around the morass of oppression, violence, and insensitivity that confronts us. Nor is he lamenting our ruin and loss. No! He is reveling in drunken and drugged-out disregard and disdain. His burning question to the reader is, "What is your drug of choice?" Those committed to dissipation and futility will smile and say, "Yes! That's the main question. Why not? What else is there?"

Yes indeed! Many people feel this way, and I have too, on occasion. But the fact that people think this is an honest response, and not merely honest but worthy of a whole poetics; this is what causes me to worry about our state of affairs.

And this fact takes us into the real inner workings of dishonesty and cynicism in this poem: the fable that has long equated inspiration with madness. This idea, articulated at least as long ago as German "Sturm and Drang" and found in English romanticism (although none of the romantics I've read were mad), became the calling card of dada and surrealism and their numerous offshoots. It is embedded in the popular mythologizing about the artist, in spite of the fact that one is hard-pressed to find meaningful examples. With a notable exception or two, like Nerval, the best we can do is point to some second-rate writers and local losers like Pound and Artaud and Plath. Ginsberg has simply summed up a long history of illusion and sloppy thinking. If we take Howl seriously we can only conclude that art and literature are degenerate, self-destructive activities, and that imagination and creativity are signs of disease, worthy of close medical monitoring at their first appearance. And yet this foolishness is the modus operandi of Howl, and a cornerstone of the poetic imagination of this century.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Concerning Allen Ginsberg's poem "Howl", part 1 of 3

Excavating my notebooks, I found this little essay on Ginsberg's Howl written in 1999. Perhaps I am ranting some [smile], but I think it's interesting reading. I’ll upload it in 3 parts. Here’s the first

Lies, Illusion, Fake Madness, Fake Art

Part 1

Lies, illusion, fake madness, and fake art: that's what our poetics and art theorists have passed on to yet another generation. Exemplified, but by no means originating in Ginsberg's so-called epic, Howl, it is summarized quite neatly in the first line: "I have seen the best minds of my generation...." Reading these words, you can put the book down. Everything that follows is mere hysterics.

This line embodies four lies, and can thus be taken as a defining statement of the artistic and intellectual cul-de-sac we have long been caught in, like those stories of lost hikers we have all heard, who wander round and round in a rather narrow circle, entirely unaware that they are going nowhere and doing absolutely nothing to help themselves, in spite of all their effort.

In what follows, I lay out the four lies Ginsberg has reproduced so cleverly in his poem. I say "reproduced" because there's nothing new here. And I say "cleverly" because by all sales measures, this is one of the most successful poems ever published. Already a second generation is gobbling it up like so much fast food.

The first lie is on the literal level. It is quite obvious and direct. Ginsberg is not describing the best minds of his, or any generation. These are the failed and broken minds and souls of his generation. These are the rejected ones, who are rejecting the world (and themselves), as much as the world is rejecting them.

The truth is anathema to the four-tiered lie Ginsberg has built. The truth is that the best minds for many generations now have been disgusted by art and literature and its futile and impotent and nay-saying view of the world. The best minds have turned to science, math, and occasionally spiritual matters. The best minds have not given up on the world, but rather, are determined to rebuild it. They have left art and literature to wallow in its own drunken swill. With this line of Ginsberg's we get a good lungfull of the smell of modern literature. With catch-phrases like ,"It's not the artist's job to create meaning; that's the job of the reader," we get another deep breath of the same vomit.

Lies, Illusion, Fake Madness, Fake Art

Part 1

Lies, illusion, fake madness, and fake art: that's what our poetics and art theorists have passed on to yet another generation. Exemplified, but by no means originating in Ginsberg's so-called epic, Howl, it is summarized quite neatly in the first line: "I have seen the best minds of my generation...." Reading these words, you can put the book down. Everything that follows is mere hysterics.

This line embodies four lies, and can thus be taken as a defining statement of the artistic and intellectual cul-de-sac we have long been caught in, like those stories of lost hikers we have all heard, who wander round and round in a rather narrow circle, entirely unaware that they are going nowhere and doing absolutely nothing to help themselves, in spite of all their effort.

In what follows, I lay out the four lies Ginsberg has reproduced so cleverly in his poem. I say "reproduced" because there's nothing new here. And I say "cleverly" because by all sales measures, this is one of the most successful poems ever published. Already a second generation is gobbling it up like so much fast food.

The first lie is on the literal level. It is quite obvious and direct. Ginsberg is not describing the best minds of his, or any generation. These are the failed and broken minds and souls of his generation. These are the rejected ones, who are rejecting the world (and themselves), as much as the world is rejecting them.

The truth is anathema to the four-tiered lie Ginsberg has built. The truth is that the best minds for many generations now have been disgusted by art and literature and its futile and impotent and nay-saying view of the world. The best minds have turned to science, math, and occasionally spiritual matters. The best minds have not given up on the world, but rather, are determined to rebuild it. They have left art and literature to wallow in its own drunken swill. With this line of Ginsberg's we get a good lungfull of the smell of modern literature. With catch-phrases like ,"It's not the artist's job to create meaning; that's the job of the reader," we get another deep breath of the same vomit.

Friday, September 29, 2006

Wordless voices

Something I've been working on during these Days of Awe:

The vois ov God-Seel sownz lusid.

Porz us, a wine in fine kut kristel,

A blu blak prizzem tu krimsen vilet.

Opake in its deep tranzlusen.

We dreenk this wine

And mezher the taest

In shaedz ov sweetlee bitterz.

But the God wine krusht

Frum the robust God-Vine

Iz not reddee,

Iz lak ov boddee

Till it lay in kask

In its blak lase shrowd

Waeten tu pass the gaetwayz

Ov its kemmek tranzmigratenz.

Oenlee then the taest and the dizzy wunder...

Hu woud reveelen?

And hu woud beleeven?

The God-Werd, self-werd, fals-werd, un-werd

Vois.

The vois ov God-Seel sownz lusid.

Porz us, a wine in fine kut kristel,

A blu blak prizzem tu krimsen vilet.

Opake in its deep tranzlusen.

We dreenk this wine

And mezher the taest

In shaedz ov sweetlee bitterz.

But the God wine krusht

Frum the robust God-Vine

Iz not reddee,

Iz lak ov boddee

Till it lay in kask

In its blak lase shrowd

Waeten tu pass the gaetwayz

Ov its kemmek tranzmigratenz.

Oenlee then the taest and the dizzy wunder...

Hu woud reveelen?

And hu woud beleeven?

The God-Werd, self-werd, fals-werd, un-werd

Vois.

Monday, September 25, 2006

O Priesthood, O Prophets, will you not find your Voice?

Listening to the last instrumental strains of Hendrix at Woodstock, and I think of music in the higher worlds... with echos of flamenco, Spanish Castle Magic, and the trope for Lamentations...

Kinder, Prepare Yurselz

We hav lernd:

Thare wuz wuns a map that charted the suwwerz

Beneeth the ruwinz ov the Vorsaw getto.

And thare wuz wuns a map that shoed the tunnelz

Owt ov Yerushalliyim tu the Yavna Yesheva.

And thare wuz wuns a text that charted the lojjek

Frum the Vois on Sini tu the orel Torra.

But all that remaenz ar the nervwayz tu the braen

And haf remember dreemz in the twilite ov owwer day.

For yu fiend yurself in this loenlee way

And see my foutprints; how far will thay go?

Yu tuu will be marvel how faent ar the traelz

In the wilderness serrownding the ruwenz ov Ewrope.

So I inkwiyerd all the Sajen wut I kno,

"Tell me, wut ar the sienz and wen will be vizhen?

"Wut will be the See and ware will we immers?"

I loukt tu the see hu woud speek,

But all ternd awway , hoelding thaer silensez.

O Preesthoud, O Proffets, will yu not fiend yur Vois?

We ar lern

Eech persen seez akkording tu the powwer tu abzorb.

Rabbi Sara bat Rute askt,

"Wut ar the Bouks ov the Lor

"Thar fallen thru owwer Sol, now loss?"

And Rabbi Dillen ben Zimmerman askt,

"Wut ar the Bouks ov the Lor

"Wuns rote but now blowing in a wind?"

And Rabbi Shlomo Karleebakh askt,

"Wut ar the Werdz ov the Lor

"Reveeld but nevver rekord?"

And Zalmen ben Sha-uel,

"Hu ar the Proffets that ar speken

"In owwer dayz huze trueth is not yet emerj?"

But Rabbi Yosee sed,

"Nuthing iz be loss,

"But oenlee owwer powwer tu open owwer Iy.

"Nuthing haz bin forgot, and nuthing remaenz unherd,

"Oenlee waeting owwer klarefyd deziyer tu knowen."

Here I am, resseld aggenst this dreemen

Tu glimps a Moment, awake....

Kinder, Prepare Yurselz

We hav lernd:

Thare wuz wuns a map that charted the suwwerz

Beneeth the ruwinz ov the Vorsaw getto.

And thare wuz wuns a map that shoed the tunnelz

Owt ov Yerushalliyim tu the Yavna Yesheva.

And thare wuz wuns a text that charted the lojjek

Frum the Vois on Sini tu the orel Torra.

But all that remaenz ar the nervwayz tu the braen

And haf remember dreemz in the twilite ov owwer day.

For yu fiend yurself in this loenlee way

And see my foutprints; how far will thay go?

Yu tuu will be marvel how faent ar the traelz

In the wilderness serrownding the ruwenz ov Ewrope.

So I inkwiyerd all the Sajen wut I kno,

"Tell me, wut ar the sienz and wen will be vizhen?

"Wut will be the See and ware will we immers?"

I loukt tu the see hu woud speek,

But all ternd awway , hoelding thaer silensez.

O Preesthoud, O Proffets, will yu not fiend yur Vois?

We ar lern

Eech persen seez akkording tu the powwer tu abzorb.

Rabbi Sara bat Rute askt,

"Wut ar the Bouks ov the Lor

"Thar fallen thru owwer Sol, now loss?"

And Rabbi Dillen ben Zimmerman askt,

"Wut ar the Bouks ov the Lor

"Wuns rote but now blowing in a wind?"

And Rabbi Shlomo Karleebakh askt,

"Wut ar the Werdz ov the Lor

"Reveeld but nevver rekord?"

And Zalmen ben Sha-uel,

"Hu ar the Proffets that ar speken

"In owwer dayz huze trueth is not yet emerj?"

But Rabbi Yosee sed,

"Nuthing iz be loss,

"But oenlee owwer powwer tu open owwer Iy.

"Nuthing haz bin forgot, and nuthing remaenz unherd,

"Oenlee waeting owwer klarefyd deziyer tu knowen."

Here I am, resseld aggenst this dreemen

Tu glimps a Moment, awake....

Sunday, September 24, 2006

The brooks prophesy...

Well, uh, maybe it's like this...

A Berd at Reb Ternerz Windo

I stumbel thru this narrel forres

Weeping, los, heer, enshrowden in addom.

Wuns I stoud uppon a hi hill

Louking over theze shaddowee vaelz.

The russelling leevz chant thaer lammentaten.

The brouks proffesy, a gergel in my eer.

I karee my noetbouk like a reffugee hiz trunk.

Am I wokking in serkelz? This Forres! Theze Voisez!

Till a lite braeks thru theze branchen, diffracten,

A thowzen pathwayz in the moment ov hope.

A lite, a border in the vannetteez and vienz.

A ragged begger noks on a dor.

Branchez trembel az I peer akross,

The begger appeering, disappeering, branch-born.

The dor openz, a suffuzen in lite.

"Kum in, my fren; I hav bin waeting.

"Yu karee a messij within yur kloek.

"If yu giv it tu me, I will take it ferther.

"Let us bless bred and exchaenj mellodeez.

Like a berd on a branch, I lissen at the windo:

"The messij I karee, hav yu alreddee herd?

"A hundred, a thowzen ar breenging it heer.

"Iz it chans or perpos that yu heer it frum me?

"Like a berd on a branch in a flok ov berdz,

"Yu heer the mellodee az I am sing.

"Iz it chans or perpos that the flock fillz a tree?

"Perpos or chans that it floks awway?

"And yu ar ammung annuther thowzen,

"Yu, allone; reheers it in yur sellz.

Like blowing leevz Yur voisez russel.

Like a gergelling brouk Yu sing.

And I hu wonderz the forres, morning,

I, tuu, karee Yur vers tu the werl.

A Berd at Reb Ternerz Windo

I stumbel thru this narrel forres

Weeping, los, heer, enshrowden in addom.

Wuns I stoud uppon a hi hill

Louking over theze shaddowee vaelz.

The russelling leevz chant thaer lammentaten.

The brouks proffesy, a gergel in my eer.

I karee my noetbouk like a reffugee hiz trunk.

Am I wokking in serkelz? This Forres! Theze Voisez!

Till a lite braeks thru theze branchen, diffracten,

A thowzen pathwayz in the moment ov hope.

A lite, a border in the vannetteez and vienz.

A ragged begger noks on a dor.

Branchez trembel az I peer akross,

The begger appeering, disappeering, branch-born.

The dor openz, a suffuzen in lite.

"Kum in, my fren; I hav bin waeting.

"Yu karee a messij within yur kloek.

"If yu giv it tu me, I will take it ferther.

"Let us bless bred and exchaenj mellodeez.

Like a berd on a branch, I lissen at the windo:

"The messij I karee, hav yu alreddee herd?

"A hundred, a thowzen ar breenging it heer.

"Iz it chans or perpos that yu heer it frum me?

"Like a berd on a branch in a flok ov berdz,

"Yu heer the mellodee az I am sing.

"Iz it chans or perpos that the flock fillz a tree?

"Perpos or chans that it floks awway?

"And yu ar ammung annuther thowzen,

"Yu, allone; reheers it in yur sellz.

Like blowing leevz Yur voisez russel.

Like a gergelling brouk Yu sing.

And I hu wonderz the forres, morning,

I, tuu, karee Yur vers tu the werl.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

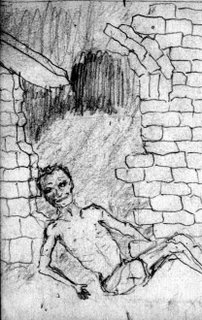

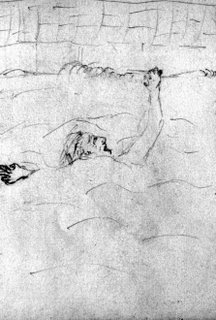

3 Images for A Pilgrimmage to Mecca

School startup has kept me too busy to attend to this blog. Hopefully I’m back in the swing again.

In this post I have uploaded 3 sketches for my story A Pilgrimmage to Mecca, a story I wrote in 1977. I haven’t yet produced the completed manuscript. Ah well. What’s 30 years in the grand sweep of events?

Actually, this manuscript has a story behind the story. I was traveling with my wife thru Turkey in the summer of 1977, while she was doing preliminary research for her Ph.D. We were there a little over 2 months, well off the beaten paths. Actually, in those days, Turkey didn’t have too many beaten paths, and we often didn’t see any other Westerners for a week or more at a time. Like the rural districts of most countries, the interior of Turkey was deeply religious and pretty fundamentalist (tho the people were in no way hostile or unpleasant to us). In those days fundamentalism of any stripe was unusual, and I grappled to understand it and give it a context that made sense to me. The result was a little story, A Pilgrimmage to Mecca.

However, when I got back to the US, I dove into new work and totally forgot about the story. About 5 years later I was going thru my old notebooks, looking for earlier ideas and images for a new poem I was beginning to work on. I discovered A Pilgrimmage to Mecca, but strangely, had absolutely no recollection of writing it. It was like pure found art. Truly, I couldn’t believe I had written it and then forgotten about it. It was such a beautiful little gem. Only after months of thinking about it, was I able to reconstruct a memory of writing the story and the motivation behind it.

However, when I got back to the US, I dove into new work and totally forgot about the story. About 5 years later I was going thru my old notebooks, looking for earlier ideas and images for a new poem I was beginning to work on. I discovered A Pilgrimmage to Mecca, but strangely, had absolutely no recollection of writing it. It was like pure found art. Truly, I couldn’t believe I had written it and then forgotten about it. It was such a beautiful little gem. Only after months of thinking about it, was I able to reconstruct a memory of writing the story and the motivation behind it.

So here are three drawings of scenes near the end. But have no fears. The hero doesn’t die!

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Repitition of Isaiah, to the Palestinians

Mishneh Yesheyawhu

Shabbut Devarim,

I hav hezzettaten, o Lor, my Lor,

Long my refraen that woud speek with Yur Namen.

Tuu theengz ar see az I stand in Yur Tempel:

The Preesthoud a marchen tu its Kubballut Shabbut**

** The reception of the Sabbath;

The greeting of the Divine Presence.

And a suwasside pepel a rebellen at Yur Glorree.**

The Preesthoud will usher in the day a Shabbut,

Karrying the Teechingz in its arks ov lite;

Baring its arks thru the terratorreez

Ware the wield ass wunse brayd and kikkt,

Hem hu ar run frum hem hart-serchen Master,

Will be fownd a benden, bowwend tu a yoke.

Pallestinnee! How long will yu sin befor yur God?

The God Yisroyel haz reveelen tu yu?

Appall! A nashen that wunse knu Merseefill,

Now vommitting haetred, now a slither in awful,

Fallen bakwerd tu a pagan faeth.

Yisroyel, louk! And be not prowd.

Yu passt this way yursellz befor.

Wy ar yu beeten yet kontinnew tu rebell?

Yesheyawhu 1:5

Yur land groez mor dessolate day by day.

Yur vinyerdz ar wither, yur sitteez dekayd.

Az a gardenner powndz a krakt pot intu rubbel,

Yu batter teenajerz intu suwasside merder

And baree yur yung wunz in liez and despaer.

Du yu kare nuthing that yu exteengwish yur fewcher?

Du yu not smell it, duz it not choke yu,

That yur suwassiedz ar a drawn owt gasp ov falure?

Yu herree, yu rase tu rezembel Siddoem.**

** Hebrew for "Sodom"

Yisroyel Preesthoud, louk uppon theze theengz.

See the ruwen, the evolvenz ov hate.

Wut ar yur sakrafishel merterz tu Me?

I am sik with yur offeringz ov kidz blud and kersez.

Vile ar yur offeringz and berning tiyerz

Az yu fowl my Kort, Yerushalliyemz streets.

Yisroyel Preesthoud, see the ruwen,

The rezult ov fals faeth and arrogans.

Fillisteya! Fallashteya! I weeree ov yu!

Klenz yursellz; remuve the evel ov yur deedz.

Yesheyawhu 1:16

Kum, let us debate the kase ov justis,

But if yu make a vilens I will be a devowwer!

Yisroyel be not smug or hard-harten.

Insted ov Me, will yu tern tu Ejipt

Hu starvd yu and kikt yu and krusht yu in Gozza,

And kloezd its borderz entiyer tu yu?

Or tu Sereya and Libnon hu hav lokt yu in kamps**

** sum say "charnelz"

Hu strip yu and wip yu and blame the Jewz?

Or tu Eron and Arrabeya hu stoke yu tu wor

Wile safe and sinnikkel and saddistek thay gorj?

Yisroyel, yu passt this way yursellz.

Fast on Tisha Ba'Av, fast and remember.

But the oenlee wunz hu woud bild yu up,

Yu kers and vow tu drive intu the see.

Pallestinneyan! Louk how yu rase tu be exteenkt.

Shorlee this iz the Hand ov God!

Yisroyel Preesthoud, louk uppon theze theengz.

See the ruwen, the evolvenz ov hate,

The rezult ov fals faeth and arrogans.

Yisroyel, louk! And be not prowd.

Yu passt this way yursellz befor.Fast on Tisha Ba'Av, fast and remember.

Yisroyel be not smug or hard-harten.

The prufe ov the Preesthoud ar deedz ov pese,

Tollerraten the mennee Hullekhaz** tord the Wun.

** Laws; paths

Yisroyel will be a redeemer in justis;

Yerushalliyem in merseez owwer Eternez Plase.

Shabbut Devarim,

I hav hezzettaten, o Lor, my Lor,

Long my refraen that woud speek with Yur Namen.

Tuu theengz ar see az I stand in Yur Tempel:

The Preesthoud a marchen tu its Kubballut Shabbut**

** The reception of the Sabbath;

The greeting of the Divine Presence.

And a suwasside pepel a rebellen at Yur Glorree.**

The Preesthoud will usher in the day a Shabbut,

Karrying the Teechingz in its arks ov lite;

Baring its arks thru the terratorreez

Ware the wield ass wunse brayd and kikkt,

Hem hu ar run frum hem hart-serchen Master,

Will be fownd a benden, bowwend tu a yoke.

Pallestinnee! How long will yu sin befor yur God?

The God Yisroyel haz reveelen tu yu?

Appall! A nashen that wunse knu Merseefill,

Now vommitting haetred, now a slither in awful,

Fallen bakwerd tu a pagan faeth.

Yisroyel, louk! And be not prowd.

Yu passt this way yursellz befor.

Wy ar yu beeten yet kontinnew tu rebell?

Yesheyawhu 1:5

Yur land groez mor dessolate day by day.

Yur vinyerdz ar wither, yur sitteez dekayd.

Az a gardenner powndz a krakt pot intu rubbel,

Yu batter teenajerz intu suwasside merder

And baree yur yung wunz in liez and despaer.

Du yu kare nuthing that yu exteengwish yur fewcher?

Du yu not smell it, duz it not choke yu,

That yur suwassiedz ar a drawn owt gasp ov falure?

Yu herree, yu rase tu rezembel Siddoem.**

** Hebrew for "Sodom"

Yisroyel Preesthoud, louk uppon theze theengz.

See the ruwen, the evolvenz ov hate.

Wut ar yur sakrafishel merterz tu Me?

I am sik with yur offeringz ov kidz blud and kersez.

Vile ar yur offeringz and berning tiyerz

Az yu fowl my Kort, Yerushalliyemz streets.

Yisroyel Preesthoud, see the ruwen,

The rezult ov fals faeth and arrogans.

Fillisteya! Fallashteya! I weeree ov yu!

Klenz yursellz; remuve the evel ov yur deedz.

Yesheyawhu 1:16

Kum, let us debate the kase ov justis,

But if yu make a vilens I will be a devowwer!

Yisroyel be not smug or hard-harten.

Insted ov Me, will yu tern tu Ejipt

Hu starvd yu and kikt yu and krusht yu in Gozza,

And kloezd its borderz entiyer tu yu?

Or tu Sereya and Libnon hu hav lokt yu in kamps**

** sum say "charnelz"

Hu strip yu and wip yu and blame the Jewz?

Or tu Eron and Arrabeya hu stoke yu tu wor

Wile safe and sinnikkel and saddistek thay gorj?

Yisroyel, yu passt this way yursellz.

Fast on Tisha Ba'Av, fast and remember.

But the oenlee wunz hu woud bild yu up,

Yu kers and vow tu drive intu the see.

Pallestinneyan! Louk how yu rase tu be exteenkt.

Shorlee this iz the Hand ov God!

Yisroyel Preesthoud, louk uppon theze theengz.

See the ruwen, the evolvenz ov hate,

The rezult ov fals faeth and arrogans.

Yisroyel, louk! And be not prowd.

Yu passt this way yursellz befor.Fast on Tisha Ba'Av, fast and remember.

Yisroyel be not smug or hard-harten.

The prufe ov the Preesthoud ar deedz ov pese,

Tollerraten the mennee Hullekhaz** tord the Wun.

** Laws; paths

Yisroyel will be a redeemer in justis;

Yerushalliyem in merseez owwer Eternez Plase.

Friday, September 01, 2006

Passing the Fox's Den

This is the opening poem to the 3-book series, Ammung the Ruwenz ov the Tempel, I Herd.....

Passing the Foxxez Den, Yerrushalliyem

Tu Yu I kall, hors and hopeless.

Yu I kall.

How mennee tiemz

Hav I stoud here befor, week and afraed?

Yu, Yu hu hav bin kwik tu anser,

Hu hav sed nuthing, and yet

The fors ov Yur Prezzens

Haz blone me akross oeshenz,

Haz exxield me frum my beluvved sittee,

Haz sent me seeking with my famlee

And all my broken thingz and saekred bouks.

Yu I kall aggen.

Now pray, I hav vencherd tu rekwest aggen,

Hu am but erth and ashez.

Dare I speek, the feer ov choking?

Dare I ask for mor than I hav?

How kan I kno

That I am werthee tu stand in this plase,

Yur Plase, tu heer Yur werdz,

And pass them on?

Passing the Foxxez Den, Yerrushalliyem

Tu Yu I kall, hors and hopeless.

Yu I kall.

How mennee tiemz

Hav I stoud here befor, week and afraed?

Yu, Yu hu hav bin kwik tu anser,

Hu hav sed nuthing, and yet

The fors ov Yur Prezzens

Haz blone me akross oeshenz,

Haz exxield me frum my beluvved sittee,

Haz sent me seeking with my famlee

And all my broken thingz and saekred bouks.

Yu I kall aggen.

Now pray, I hav vencherd tu rekwest aggen,

Hu am but erth and ashez.

Dare I speek, the feer ov choking?

Dare I ask for mor than I hav?

How kan I kno

That I am werthee tu stand in this plase,

Yur Plase, tu heer Yur werdz,

And pass them on?

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Siegfried as the German Soul

Meshal* of the Nebelungen

*A meshal is a Rabbinic literary form, a parable including its interpretation

The foreign warrior enters the land of an unfriendly king, for the sake of marrying the king's daughter. The sons of the king, admiring the foreign warrior's strength, befriend him and make a place for him as a vassal. The warrior marries the daughter of the king, the sister of the king's sons. This warrior grows stronger, surpassing the king in both strength and wealth. Now the son's wives grow jealous, and the king's court envious. They plot to assassinate the foreign vassal, and on doing so, expropriate his wealth.

The wife of the murdered vassal joins league with, and marries a warlike pagan neighbor. She hopes to inflict revenge, and also regain her wealth. She lures her brothers-in-law into her pagan court, where the king has them murdered. Then the queen murders her children by that pagan king, and then murders the king himself, bringing ruin on both houses.

There is another side to this history. It is the side we read in the history books:

There is a man whom many honor. He murders his wife. While his brothers and sisters, his friends, his teachers stand by his side, he murders her, coldly, cruelly. It was not unexpected, had anyone considered his behavior. One day he scorns her; then he degrades her; finally, in the light of day he murders her.

Who was this man? He was Europe, and his wife was Yisroyel. Though the man was brought to justice, what of his siblings, friends, and neighbors? What of his teachers?

But, you may ask, what does this have to do with the story of the king, the murdered vassal, and the revenge brought down by the vassal's wife? The first story is a spiritual history, with motivations, causes and effects. The second story is its political version, its outward events and the questions and doubts one is left with. But it is the same story. In the spiritual version, the king is a composite of many European rulers. The vassal is Yisroyel. The vassal's wife is the Divine Shekhena. Europe's crimes will not go unpunished, but, naturally, it will be God, not Yisroyel that will effect that punishment. In other words, the Divine reckoning will be invisible. The historians will record Europe's political and economic decline, and will find local, tenuous causes, but the spiritual causality of Europe's rise and then its ruin will remain unseen and unaccounted.

*A meshal is a Rabbinic literary form, a parable including its interpretation

The foreign warrior enters the land of an unfriendly king, for the sake of marrying the king's daughter. The sons of the king, admiring the foreign warrior's strength, befriend him and make a place for him as a vassal. The warrior marries the daughter of the king, the sister of the king's sons. This warrior grows stronger, surpassing the king in both strength and wealth. Now the son's wives grow jealous, and the king's court envious. They plot to assassinate the foreign vassal, and on doing so, expropriate his wealth.

The wife of the murdered vassal joins league with, and marries a warlike pagan neighbor. She hopes to inflict revenge, and also regain her wealth. She lures her brothers-in-law into her pagan court, where the king has them murdered. Then the queen murders her children by that pagan king, and then murders the king himself, bringing ruin on both houses.

There is another side to this history. It is the side we read in the history books:

There is a man whom many honor. He murders his wife. While his brothers and sisters, his friends, his teachers stand by his side, he murders her, coldly, cruelly. It was not unexpected, had anyone considered his behavior. One day he scorns her; then he degrades her; finally, in the light of day he murders her.

Who was this man? He was Europe, and his wife was Yisroyel. Though the man was brought to justice, what of his siblings, friends, and neighbors? What of his teachers?

But, you may ask, what does this have to do with the story of the king, the murdered vassal, and the revenge brought down by the vassal's wife? The first story is a spiritual history, with motivations, causes and effects. The second story is its political version, its outward events and the questions and doubts one is left with. But it is the same story. In the spiritual version, the king is a composite of many European rulers. The vassal is Yisroyel. The vassal's wife is the Divine Shekhena. Europe's crimes will not go unpunished, but, naturally, it will be God, not Yisroyel that will effect that punishment. In other words, the Divine reckoning will be invisible. The historians will record Europe's political and economic decline, and will find local, tenuous causes, but the spiritual causality of Europe's rise and then its ruin will remain unseen and unaccounted.

The definitive function of true art

More on "My" Language

If you have come this far, you know that language is not fixed, it is not complete; indeed it is merely (dare I say "merely?) an approximation to reality, our personal realities and our shared ones. In this light I would assert that language is one, but only one of the "connective tissues" that help build interpersonal realities.

I have tried to show, without the clutter and excess baggage of theory, but rather existentially, that words need not be thought of as bricks to build with, but clay to sculpt with. And a truly wonderful clay! It is soft and malleable to those who think it so. It is stiff and resistant if so imagined, for those whose "hands" are weak or untrained.

Perhaps it would be well to acknowledge my own errors and failures, instead of casting aspirins. When I compose, and until I'm compelled to produce a fair copy so others can have some hope of following my threads, my drafts are filled with innumerable alternative words, phrases, and images. Reducing this multi-layered mosaic into readable images is necessary, but inevitably diminishes the depth of those images. That is because in some cases there are no right words (at least that I am privy to), or there are many partly right words. So my poems suffer from inaccuracy and incompleteness.

When I am being more or less successful, each word is a vertex (or is it a vortex?) connecting vectors from multiple layers of reality. Their purpose is to expose, not conceal, those layers. This makes reading me slow going, but if one desires to truly understand reality, and not simply get by with the minimum amount of necessary awareness, every moment, every thought, every feeling, every word, quite obviously, is connected to a vast network of related "nodes."

Too often I have not made those connections, or I've only made a few when many were possible. More problematic is when I have been inaccurate. I have distorted or muddied reality, rather than clarifying it. Therefore, I can only rely on you to correct me or expand upon the narrow apertures I've tried to open.

One final note about "reality." It is important to distinguish between the complex, incomplete, and often discontinuous images that expose reality (ie the contents of consciousness), on the one hand, and the spectrum of common and accessible conventions that are used to distort the forms of most modern "art," on the other. Modern art, on the one extreme, creates self-contained narratives that hide or deny discontinuities and contradictions. It is really a form of illusionism and unreality. Popular novels and films do this to great financial success. At the other extreme, we find self-absorbed experimentalism, in which reality, and conscience especially, have become insignificant determinants, or inconvenient obstructions. While both extremes of art, literature, and music can entertain or delight the senses, they cannot be taken as serious. The definitive function of true art is its imperative to inspire moral clarity, ethical action, and spiritual awakening.

If you have come this far, you know that language is not fixed, it is not complete; indeed it is merely (dare I say "merely?) an approximation to reality, our personal realities and our shared ones. In this light I would assert that language is one, but only one of the "connective tissues" that help build interpersonal realities.

I have tried to show, without the clutter and excess baggage of theory, but rather existentially, that words need not be thought of as bricks to build with, but clay to sculpt with. And a truly wonderful clay! It is soft and malleable to those who think it so. It is stiff and resistant if so imagined, for those whose "hands" are weak or untrained.

Perhaps it would be well to acknowledge my own errors and failures, instead of casting aspirins. When I compose, and until I'm compelled to produce a fair copy so others can have some hope of following my threads, my drafts are filled with innumerable alternative words, phrases, and images. Reducing this multi-layered mosaic into readable images is necessary, but inevitably diminishes the depth of those images. That is because in some cases there are no right words (at least that I am privy to), or there are many partly right words. So my poems suffer from inaccuracy and incompleteness.

When I am being more or less successful, each word is a vertex (or is it a vortex?) connecting vectors from multiple layers of reality. Their purpose is to expose, not conceal, those layers. This makes reading me slow going, but if one desires to truly understand reality, and not simply get by with the minimum amount of necessary awareness, every moment, every thought, every feeling, every word, quite obviously, is connected to a vast network of related "nodes."

Too often I have not made those connections, or I've only made a few when many were possible. More problematic is when I have been inaccurate. I have distorted or muddied reality, rather than clarifying it. Therefore, I can only rely on you to correct me or expand upon the narrow apertures I've tried to open.

One final note about "reality." It is important to distinguish between the complex, incomplete, and often discontinuous images that expose reality (ie the contents of consciousness), on the one hand, and the spectrum of common and accessible conventions that are used to distort the forms of most modern "art," on the other. Modern art, on the one extreme, creates self-contained narratives that hide or deny discontinuities and contradictions. It is really a form of illusionism and unreality. Popular novels and films do this to great financial success. At the other extreme, we find self-absorbed experimentalism, in which reality, and conscience especially, have become insignificant determinants, or inconvenient obstructions. While both extremes of art, literature, and music can entertain or delight the senses, they cannot be taken as serious. The definitive function of true art is its imperative to inspire moral clarity, ethical action, and spiritual awakening.

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Concerning the Third Temple

I dreemd I was holding a sheet on which were written suicide notes from Auschwitz. It was on my heart, so heavy. This is all that happened in the dreem, for a long time, altho perhaps there were also scenes of Auschwitz in the background, too. A dreem of hours, of ours.

Can we say Kaddish for these ones too? They are crying out in my Soul. They want to return to the world but they are still in traum.

Befor the Hi Preest Assenden

I askt Rabbi Yosee,

"May I even say my kwesten?"

He sed, "Sho it so yur tents kan be juj."

I ask, "Wen will we rebild the Tempel,

"And ware?"

Then Rabbi Yosee sat me down beneeth a tree

And all the leevs ov the tree wer illume,

Goelden ritingz allong thaer interkut vaenz.

He kwiklee skannd thru the jenome

And az he did, hiz fase reflekten thaer brillyen liets.

"Heer, I will giv yu the Torrah,

"But nex yu must lern its Mishneh.

"Thare ar being three Tempelz.

"The Firs the Lor haz laening in yur Soel,

"Frum its fowndaten tu its kurven rafter roof.

"The Sekken the Romanz, hu yu liv ammung,

"Ar wont tu tare down az yu ar bild.

"This iz the Tempel ov yur Praer-Staet

"And wen all the Preesthoud iz bilding

"It kumz tu kompleten.

"Wen the Praer-Staet Temple iz thronging

"And the brokade kertenz ov the Ark ar open

"The werk ov the Therd Tempel iz begin.

"Az a sine befor yur iyz:

"How far hav yu led the Naeshenz?

"Wen yu plase the nex stone

"The Naeshenz will fall on thaer fasez in aw.

"Els the stone iz not in plase."

Can we say Kaddish for these ones too? They are crying out in my Soul. They want to return to the world but they are still in traum.

Befor the Hi Preest Assenden

I askt Rabbi Yosee,

"May I even say my kwesten?"

He sed, "Sho it so yur tents kan be juj."

I ask, "Wen will we rebild the Tempel,

"And ware?"

Then Rabbi Yosee sat me down beneeth a tree

And all the leevs ov the tree wer illume,

Goelden ritingz allong thaer interkut vaenz.

He kwiklee skannd thru the jenome

And az he did, hiz fase reflekten thaer brillyen liets.

"Heer, I will giv yu the Torrah,

"But nex yu must lern its Mishneh.

"Thare ar being three Tempelz.

"The Firs the Lor haz laening in yur Soel,

"Frum its fowndaten tu its kurven rafter roof.

"The Sekken the Romanz, hu yu liv ammung,

"Ar wont tu tare down az yu ar bild.

"This iz the Tempel ov yur Praer-Staet

"And wen all the Preesthoud iz bilding

"It kumz tu kompleten.

"Wen the Praer-Staet Temple iz thronging

"And the brokade kertenz ov the Ark ar open

"The werk ov the Therd Tempel iz begin.

"Az a sine befor yur iyz:

"How far hav yu led the Naeshenz?

"Wen yu plase the nex stone

"The Naeshenz will fall on thaer fasez in aw.

"Els the stone iz not in plase."

Monday, August 14, 2006

Blessing the first born

In February of 2004, my oldest son returned to Hebrew U. in Jerusalem, amid a veritable downpour of tears. Back home, feeling the waves of sorrow, I decided to go surfing in it, and found this.

Blessen on my Elden Sun